1.0 Introduction

Heptapod A is a fictional communication system spoken by an alien species in Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life”. Heptapod B is the alien writing system that is more thoroughly investigated and understood in Chiang’s world. It is revealed that Heptapod A and Heptapod B are unrelated and the writing of Heptapod B’s ideograms are created simultaneously, building from Fermat’s Principle of Least Time which is the concept of how light chooses the fastest path to its destination (Chiang, 2015). In “Story of Your Life” this principle helped uncover the method behind Heptapod B because the fictional linguist Dr. Banks theorized that if light can choose the fastest path to its destination, then it must know its final destination beforehand, implying that time was not linear to light therefore the Heptapods may also experience time differently.

Heptapod A being an alien language can be assumed to not follow a Universal Grammar which is the innate principles all human languages share (Coon, 2020). Fortunately for us, Dr. Banks managed to uncover Heptapod B’s free word order and the aliens’ ability to produce multiple levels of centre-embedded clauses which human language has a limitation on (Chiang, 2015). Considering the constraints of multiple centre-embedded clauses may be a by-product of our short-term memory limitations (Karlsson, 2007), it makes sense that an alien with the ability to see into the future could handle the cognitive demand of producing these clauses.

Smith and Wheeldon (1999) investigated how much planning is completed (in humans) prior to articulation. Their picture-description task visualised various first clause complexities and sentence lengths, and recorded speech onset latencies to determine which forms and lengths of sentences took longer to plan. The authors believed that a complex first clause would take longer to plan than a simple clause, meaning the full first clause is in the planning scope at the point of articulation. They also believed that if two-clause sentence took longer to plan in comparisons to one-clause, then a portion of the second clause is also in the planning scope. They found not only a main effect of complexity and length, but also an interaction in the reduced complexity of long sentences compared to short. Their findings indicate that more planning is given to the first clause than the second clause.

This report will examine the grammatical and conceptual encoding of Heptapod A to understand if their spoken language produces similar results as the human English speakers in Smith and Wheeldon (1999). The Heptapod design in the film adaptation Arrival has no apparent eyes but has proven to be able to see, let alone communicate through writing, so visual stimuli will be used with a picture description task. Because Heptapod A and B are unrelated there must be an apparent distinction between their ability to produce spoken communication as the simultaneous non-linear approach to their writing cannot be construed in the sequential nature of auditory speech (Chiang, 2015). Due to their cognitive abilities, it may be possible that Heptapod A’s planning scope can be more accommodating to clausal and length variation and will not produce any main effects nor replicate the delays found in the previous study. Alternatively, if my predictions are not met and the Heptapods take longer to plan simple-complex sentences then this may tap into their unique language structure and spoken word order, violating Greenburg’s Universal Grammar which posits the shared properties of verb to object or object to verb languages.

2.0. Methods

2.1. Participants

The participants were twenty young-adult Heptapods with normal vision. All the Heptapods had similar education backgrounds, fluent in Heptapod A, and have signed their respective semasiographic names in agreement to not use their foresight to give them an advantage in the experiment.

2.2. Materials

A set of 48 black and white line drawings of familiar objects were used based on a fictional Heptapod normed list from a variety of semantic categories. All the pictures had a naming latency less than 600ms and a mean word frequency of more than 150 occurrences per million and ranged from one to two syllables in length. Following very closely to Smith and Wheeldon’s (1999) Experiment 1, 24 of the total pictures were used to create 32 sets of three pictures built two sets of sixteen which were matched for latencies and were created to avoid phonological and semantic similarity among each set. These were then combined in four different ways to produce a total of four sets (for each condition) of 8 triples. Each picture occurred in a screen position only once, and each experimental picture occurred only once in all sets. In the experiment, pictures could move either up or down. Movements are assigned to the subject phrase and object phrase where either the subject phrase moves up, and the object phrase moves down, or the object phrase moves down, and the object phrase moves up for two-clause sentences. Movements for the single clause sentences will have the subject phrase move up or own with the subject phrase having no movement. The filler picture sets will utilize additional movements: right, left, and no movement. The conditions were assigned as follows:

- complex-simple sentence: the blorp and the srup move up and the forp moves down

- simple-complex sentence: the blorp moves up and the srup and the forp move down

- complex sentence: the blorp and srup moves up

- simple sentence: the blorp moves up

Participants saw the same number of movements, and the order of these movements was randomized.

The remaining 48 objects were made into filler sets of triples to avoid the priming of the next experimental set. Staying close to Smith and Wheeldon’s (1999) study, the fillers will have four types that will elicit different responses: (1) all objects move in different directions, (2) two objects move in the same direction, (3) all objects move in the same direction, and (4) no objects appear.

2.3. Design

The independent variables are the first-clause complexity (simple-complex, complex-simple, simple, and complex) and sentence length (one-clause and two-clause). The dependent variable is the speech onset latencies (ms). First-clause variation and sentence length are both within subject and between item as all the images are grouped in certain triples that avoid phonological and semantic similarity.

2.4. Procedure

The Heptapods were tested individually in physically accommodating labs or upon their spaceships if they prefer. They were situated approximately three meters in front of a large computer monitor (Heptapods are 10m tall). They were also recorded for speech onset latencies with a sensitive voice key to accommodate for distance.

Again, like Smith and Wheeldon (1999), the experiment began with two practice blocks of 10 trials which will have each experimental picture occur once to activate the lemmas. This was followed by eight experimental blocks also featuring 10 trials. Altogether, these would create two “pairblocks” of 16 experimental trials and 24 filler trials, totalling 32 experimental trials and 48 fillers per participant.

The participants were instructed on what types of movements they would see and in what way they should be described. Because this design assumes an SVO order of Heptapod A, they were instructed to also describe the pictures from left to right. Each trial will start with a displayed central frame indicating the location and boundaries of the set of images (a triplet set). The frame will appear for 2 s and then will display the set of images. Movement of the images will begin instantly and will last up to 1000ms. As soon as the participants began to describe the set of images, triggering the voicekey, the set of images will disappear. After an increment of 4 s the next trial will begin. Breaks were encouraged, but the Heptapods deemed them unnecessary and were eager to participate.

3.0. Results

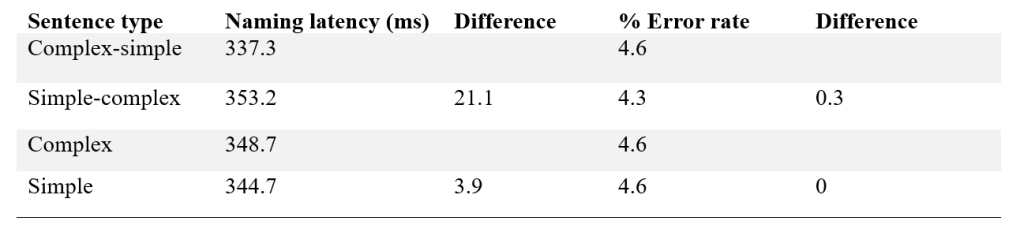

Analysis was done with a 2×2 factorial ANOVA with sentence length (simple vs. complex) as within subject and between item and first clause complexity (simple-complex vs. complex-simple) as within subject and between items. By-item analysis considered the effect of set (image used) on the onset latencies. Error rates and mean latencies will be shown in Table 1.

First, the effects of length, which includes one-clause and two-clause sentences, and the effects of first clause complexity, which included all sentence types, simple, complex, simple-complex, and complex-simple, were analysed with a 2×2 ANOVA with follow-up t-tests. Analysis revealed a main effect of first clause complexity (simple-complex, complex-simple, simple, and complex) (F (2,636) =5.664, p<.005). There was also no main effect of length (F (1,636) =.046, p=.829). Follow-up paired t-test Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons revealed there was no significant difference between simple and complex sentences, showing the main effect of type was not driven by length (p=.52). The t-tests also revealed the main effect of type was driven by the slower onset latencies of simple-complex sentences (M = 358.25, SE = 4.57) than in complex-simple sentences (M = 337.3, SE = 4.33) across all trials (t (159) = 3.6, p <.001).

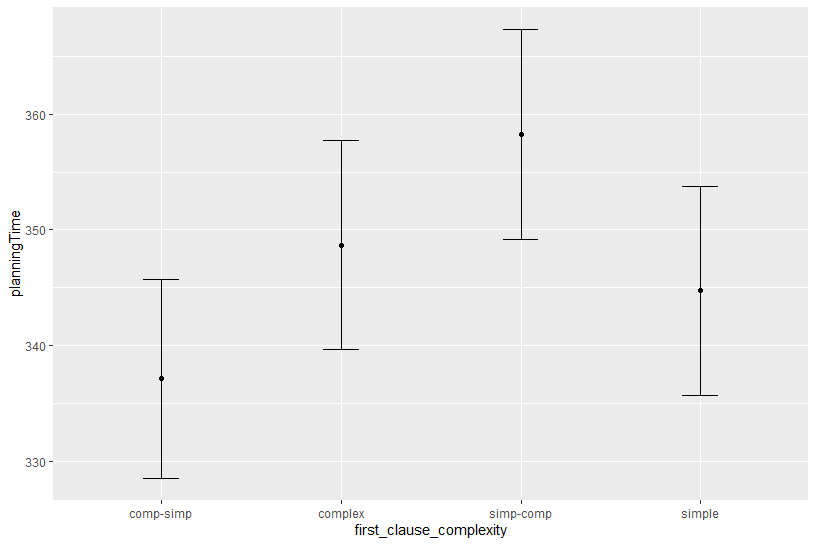

In Figure 1, the comparisons of length and complexity are shown. As stated before, though there was a slower mean onset latency for complex sentences, there were no significant differences in onset latencies for simple and complex sentences, illustrating no effect of sentence length (one-clause and two-clause), which does not successfully replicate previous findings.

First-clause complexity demonstrates a main effect, more closely shown in Figure 2. Contrary to previous studies on English-speaking humans, simple first clauses elicited slower onset latencies than complex first clauses. Interestingly, the one-clause and two-clause sentences testing for length are also slower than the three-clause complex-simple phrases. Though this difference is not significant, it is notable that there is an apparent strategic change in sentence planning for changes in sentence length.

4.0. Discussion and Conclusion

The findings indicate that Heptapod A reserves more time for planning the final clause than the first. Complex-simple sentences produced faster onset times than simple-complex sentences, when strangely the onset times were extraordinarily similar for sentences of one clause (simple) and two clause (complex) length. Considering my hypothesis of no main effect in complexity and length not being met, we must consider the possibility that Heptapod A has an entirely unpredictable planning scope. When it came to their point of articulation for single clause and double clause sentences there was a suspicious lack of significant difference which gave my main predictions a half-hearted shrug because though there was no main effect, the non-significant difference in onset latencies contradicted what I believed, following the findings in the previous studies by reporting slightly slower responses to complex phrases as opposed to simple ones were achieved in Smith and Wheeldon’s (1999) study.

So how does this fare with the findings on first-clause complexity? It appears that in larger phrases, Heptapods may switch to a strategy that has them prioritize complex phrases, given they had to describe the images left to right, so upon seeing one object in the subject phrase move, they may have taken more time to observe the object phrase items before articulation. Sentence production has been found to be flexible and not structurally fixed (Wagner, et al. 2010), so the change in strategy follows findings in previous studies. This prioritization of complex phrases could be a reflection of Heptapod B’s ability to produce multiple centre-embedded clauses. If it is not a reflection of their inter-clausal structure, then we can also consider the free-word order of Heptapod B, which is a blatant rejection of Greenburg’s Universal Grammar. The apparent slowing of onset latencies for simple-complex phrases may even illuminate a disadvantage of the sequential order of spoken language, considering the Heptapods’ simultaneous approach to writing and their experience with time.

For follow-up studies I would want to test Heptapod A’s own language structure. One of the limitations of this study includes its SVO approach. When eye-tracking technology becomes more advanced and can detect the direction of a Heptapod’s gaze, I would want to do an eye-tracking study following (Spivey, et al. 2002) to gage Heptapods’ syntactic processing in comparison to the restricted-domain serial modal and the multiple-constraint model. Using this kind of experiment on Heptapods will give us more context on how they approach their sentence planning with visual context. Their ability to simultaneously produce clauses could improve their ability in dealing with the ambiguity employed in Spivey, et al. 2002. If a full semasiographic dictionary of Heptapod B and a large corpus of Heptapod A and B become available, these symbols that look like coffee stains can be treated as an image for visual context. Rather than using picture items, the semasiographs themselves will be prompts for “picture” naming. Eye-tracking and a full understanding of their writing system can give us clues into how Heptapods approach and conceptualize their “simultaneous order”.

References

Chiang, T. (2015). Story of your life, in Stories of your life and others. Main Market Ed. (76). Picador

Coon, J. (2020). The linguistics of Arrival: Heptapods, field linguistics, and Universal Grammar, in Punske et al., Language Invention in Linguistics Pedagogy. Oxford Academic, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198829874.003.0004

Karlsson, F. (2007). Constraints on Multiple Center-Embedding of Clauses. Journal of Linguistics, 43(2), 365–392. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40057996

Smith, M., & Wheeldon, L. (1999). High level processing scope in spoken sentence production. Cognition, 73(3), 205-246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-0277(99)00053-0

Spivey, M. J., Tanenhaus, M. K., Eberhard, K. M., & Sedivy, J. C. (2002). Eye movements and spoken language comprehension: Effects of visual context on syntactic ambiguity resolution. Cognitive Psychology, 45, 447–481.

Wagner, V., Jescheniak, J. D., & Schriefers, H. (2010). On the flexibility of grammatical advance planning during sentence production: Effects of cognitive load on multiple lexical access. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 36(2), 423-440. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018619